Do you want to give marine life a hand?

Exhibit Details

Open FebNov 2021

Ground LevelStreet Gallery

- The Brief

- Let's Complicate Things

Old oil platforms might be junk in the sea, but now they have become thriving marine ecosystems. We could take them out, but that would disrupt these new habitats.

Humans can barely stop themselves from intervening with nature. Do we just need to butt out and let nature do its own thing?

Delve Deeper

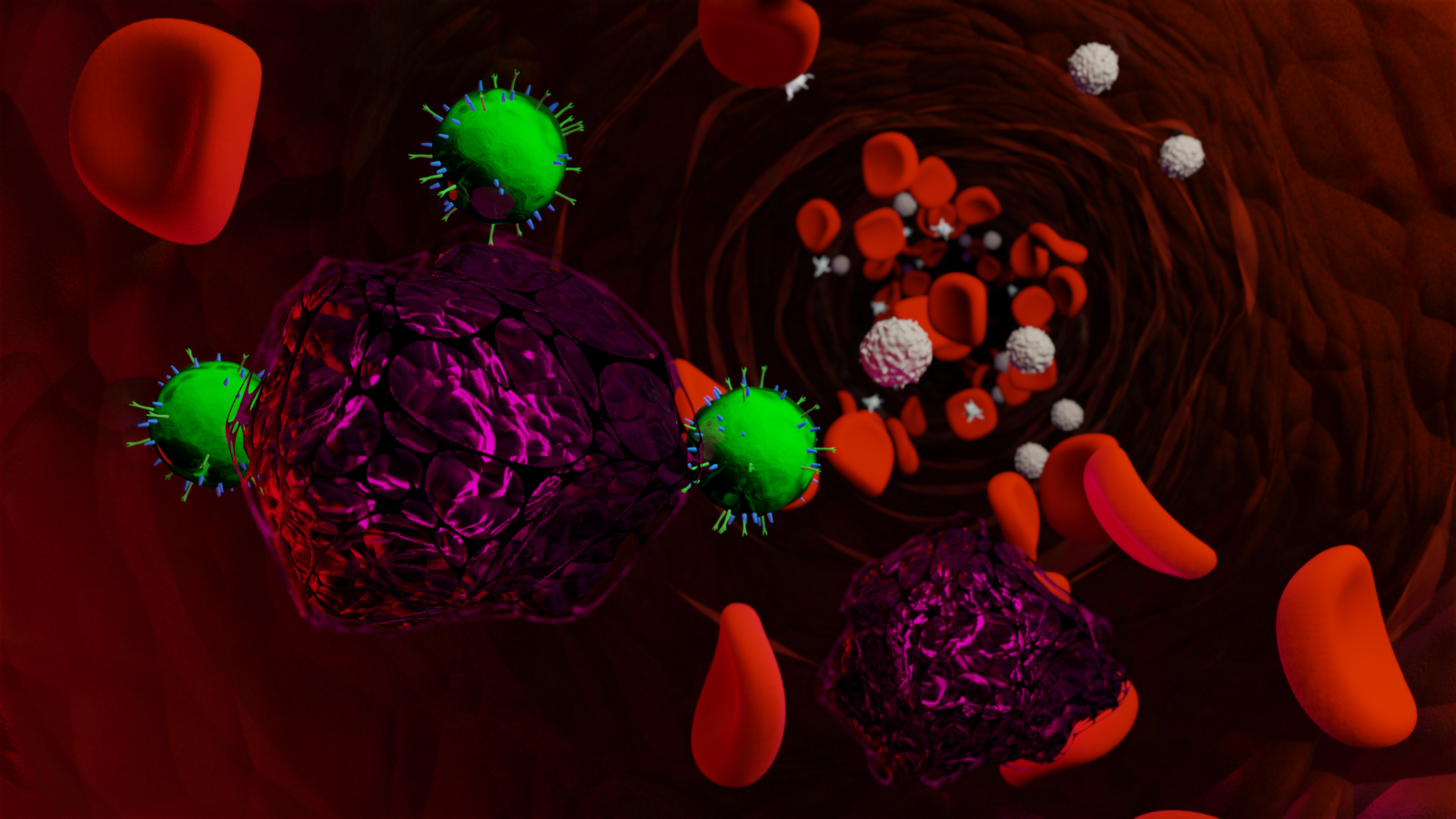

Co-evolution is likely to happen when different species have close ecological interactions with one another. It is one of the main ways biological communities are organised.

Two organisms living in close relation is called symbiosis. Symbiotic relationships include:

- Predator/prey (and parasite/host) – one species in the relationship benefits at the expense of the other(s);

- Competition – this involves intra- and interspecies competition for resources like food or shelter;

- Mutualism – both species gain benefit from the relationship.

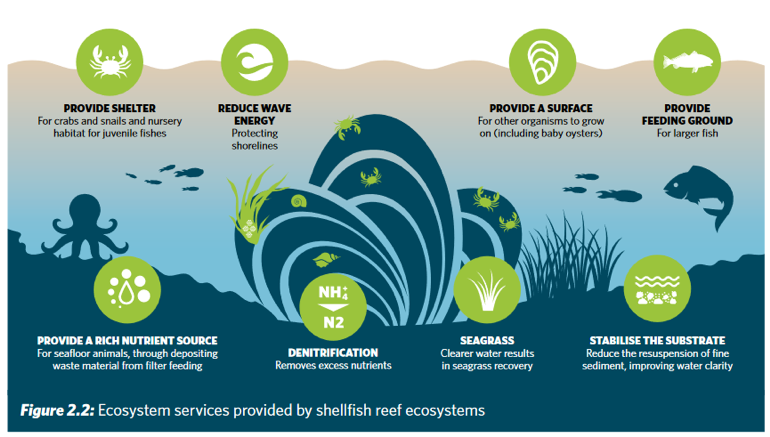

Oil platforms, seawall tiles and shellfish reefs all provide habitat where species have close ecological interactions, for example the interactions on shellfish reefs where oysters excrete a mucus-like substance that is rich in nutrients and provides food for small shellfish that in turn provide food for larger fish.

Look more into co-evolution here.

Accidentally building marine habitats – what do we do with old oil and gas platforms?

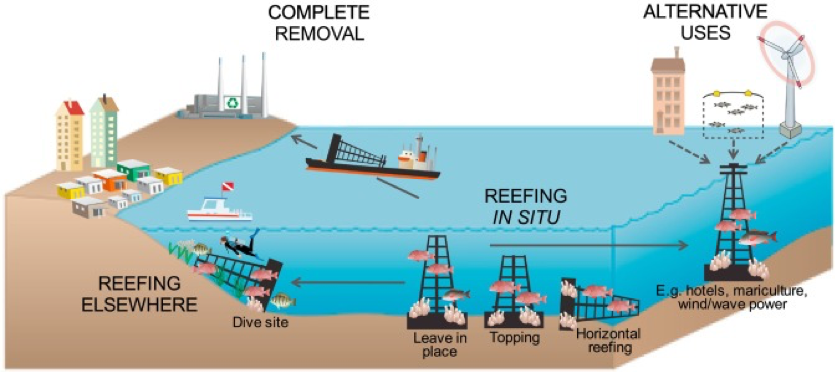

There are over 2,000 wells and 30 platforms for oil and gas production off the Australian coast, many of which are coming to the end of their working life. Then there’s the cost. Australia’s decommissioning bill is expected to be $40 billion over the next 40 years.

Now we have to figure out what we should do with these massive structures. Are they trash? Or an ocean treasure?

Some of these structures have been in place for decades and are now home to a thriving marine community of corals, invertebrates and fish. It’s not just that fish are attracted to these structures, researchers have found that they’re acting as nursery sites – lots of fish are being born there.

The benefits of leaving the structures in place include increasing numbers and biodiversity of marine life, benefits for recreational and commercial fishing (even if the sites themselves are default marine sanctuaries as they’re not suitable for commercial fishers to come near them).

So what are the options? They can be removed completely, left in place or ‘reefed’ elsewhere. There are proposals to repurpose them into other uses like recreation facilities or alternative energy production facilities for wind or wave energy. There’s a platform in Malaysia that’s been turned into a hotel and dive resort.

Leaving them where they are though, is effectively dumping waste at sea. Just because something will grow on it doesn’t mean it should stay there. No one is suggesting that we start dumping all our old cars into the ocean just because they might form an artificial reef. There’s also the issue of leaching of toxic components from the structures into the surrounding environment too. And while they are home to an abundance of life, if they are attracting or supporting invasive species, is that the best outcome?

Deliberately building marine habitat – living sea wall tiles

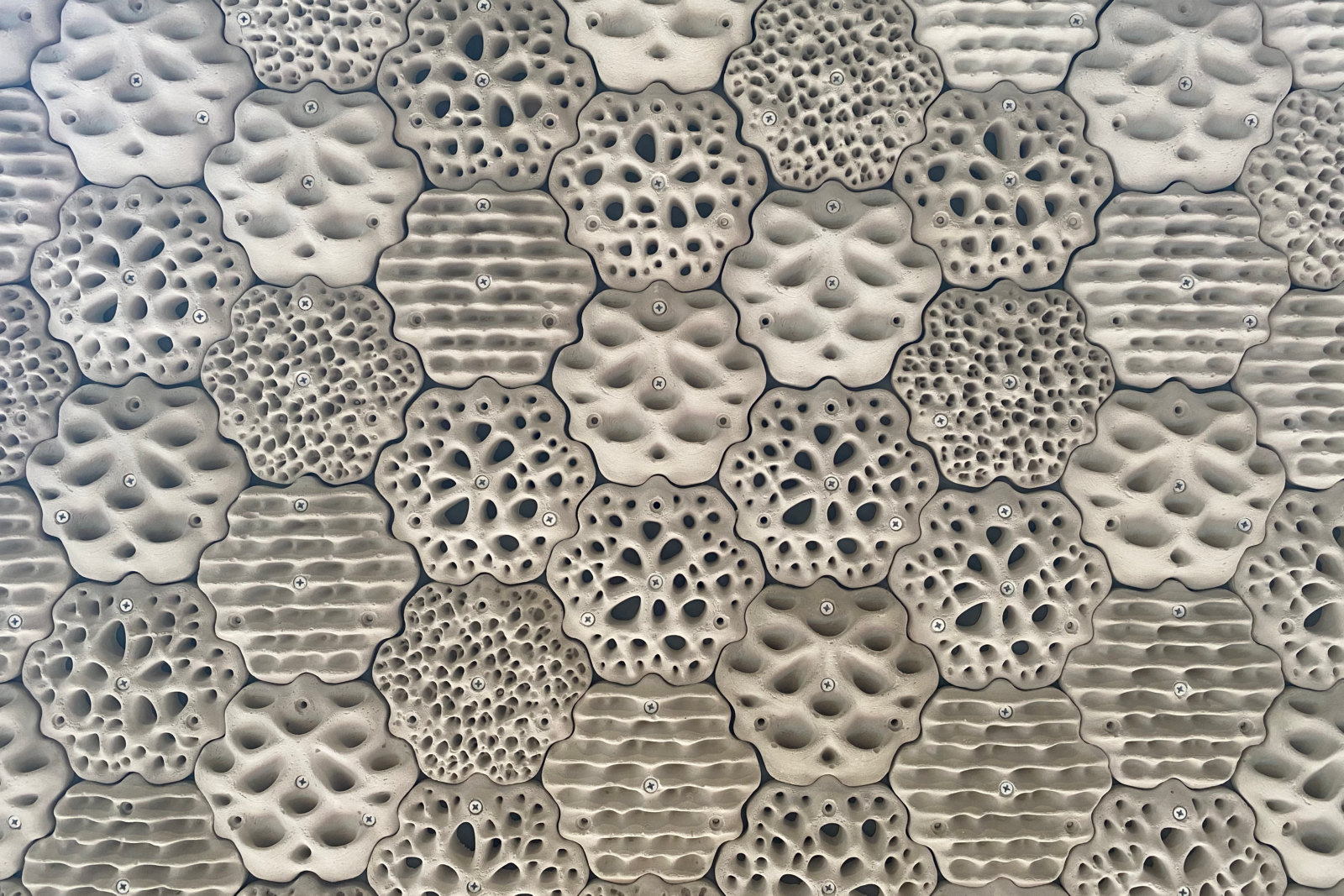

A different approach is to deliberately design and install infrastructure for marine life to live and thrive on, particularly in areas that have been impacted a lot by human development like ports.

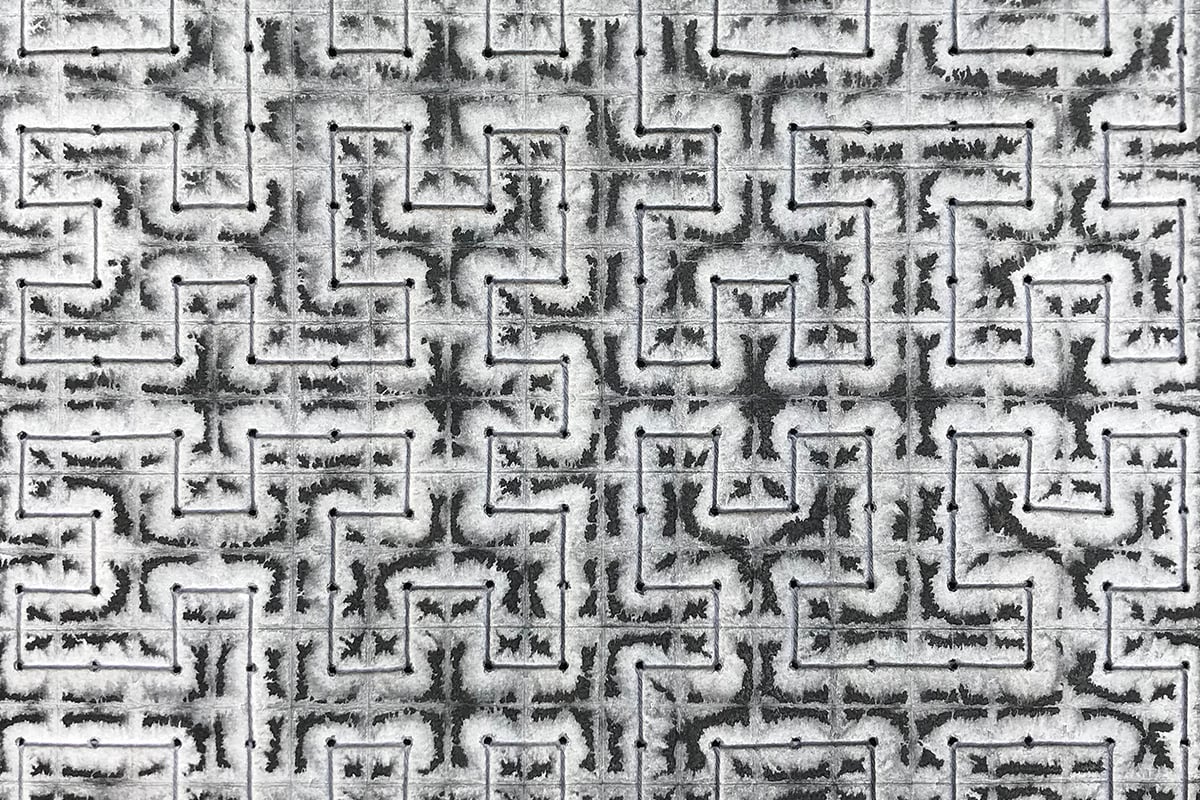

Seawalls are an ever present structure in our intertidal environments and are not designed with shelter for native marine animals in mind. Normally a seawall is completely flat and devoid of crevices minimising the potential for colonising organisms. The aim of the living seawalls project is to begin developing a blueprint for how we can design marine infrastructure in the future.

The Reef Design Lab do just this, creating 3-dimensional seawall tiles that increase surface area and provide pooling water for sea life to live, hide, feed and breed within. The complex geometry encourages biodiversity. To date, 4 tile designs have been developed, mimicking microhabitats provided by rock pools, crevices and weathered sandstone (honeycombing and swim-throughs). There are currently seawall tiles installed in Sydney Harbour and at Port Adelaide.

Let nature do its own thing – shellfish reef restoration

Here in SA we don’t get tropical coral reefs – but we did use to have thousands of km of reefs made from shellfish – that is native oysters. Over time layers upon layers of shellfish formed natural reef structures home to lots of marine life. These were virtually wiped out over the 19th and 20th Century by overfishing, dredging, pollution and disease.

Today The Nature Conservancy is leading a project to restore native shellfish reefs to South Australia. In 2017-18 the Windarra Reef was created off Ardrossan on the Yorke Peninsula, and in 2020 the second major reef was started about 1km off Glenelg. The reefs are created by laying down limestone, as the oysters need a solid base to stick to (rather than sand for example). The limestone is then seeded with millions of spats – baby oysters.

Oysters are amazing creatures. Adult native oysters can filter more than 200 litres of water a day and excrete a mucus-like substance that is rich in nutrients and provides food for small shellfish that in turn provide food for larger fish, supporting a complex ecosystem rich in biodiversity. They also stabilise the sea bed and reduce coastal erosion.

The Glenelg reef is part of The Nature Conservancy’s National Reef Building Project that aims to rebuild 60 reefs in six years across Australia.

Discover more

Watch:

Read:

Credits

- Peter Macreadie Blue Carbon Lab - Research

- Emma McKinley Cardiff University - Research

- Andrew Taylor National Energy Resources Australia (NERA) - Research

- Alex Goad Reef Design Lab - Seawall tiles

- Maria Vozzo Sydney Institute of Marine Science - Research

- Anita Nedoskyo The Nature Conservancy - Reef Restoration Research

- Studio 1 Exhibitions Build

- Walls That Talk Graphic Design

- Keiko Conservation Foundation Rigs2Reef Video content

- Sandpit Digital Interactive