Posted 29 Apr

Dr Jilda Andrews is a Yuwaalaraay woman, cultural practitioner and researcher based at ANU in Canberra. She joined us in March and April as our Futurist-in-Residence and Pembroke School Visiting Research Fellowship (VRF). Hear Jilda recount her fellowship below.

My time as Pembroke School Visiting Research Fellow was exploratory, complex, emergent and above all else, creative. The central idea I set out to investigate was around the concept of ‘two-way minded futures’. And what affordances become available when two differing structures of time are brought into dialogue with one another. I ask this with an intent of imagining strong cultural futures in a respectful, deferential, and privileged Australia. A future Australia and one that I want to belong within.

For some time I have struggled with the concept of colonialism relying heavily on the spatial dimension; dispossession, dispersal and stolen lands are concepts that dominate Australia’s complex and troubled history. Slowly Australians are coming to terms with the impacts of these things – but we still have a long way to go. Last October’s failed referendum for Constitutional Recognition for Indigenous Australians shows that the pathway ahead is far from being a well-imagined one, begging the question of ‘what next’?

So to introduce a time-dimension to colonialism and post reconciliation imaginings offers some different thinking. To consider that colonisation not only dispossesses people from their land and belonging, but it can also dispossess one from their present, presence and future belonging is something that I don’t think Australians are used to considering. If decolonising relies on reclaiming Indigenous rights to land, then surely it is also about reclaiming Indigenous rights to time – and reclaiming a future where we belong.

The 65,000 year time-stamp of continued occupation of the land by Indigenous people of Australia is a trope invoked by many. This depth of time is immense – in reality, too long for most people to imagine. We do often hear that ‘Indigenous Australians are one of the oldest living continuous cultures on the planet’. This is used to great effect when establishing the depth of occupation and connection and provides some kind of scientific and empirical anchor-point to what many Indigenous people mean when they say that they have been here since time-immemorial. This trope is significantly limited – almost undermined in fact, by our collective incapacity to imagine continuities beyond the present moment. It also does not take in to account non-linear understandings of time, and many cultural understandings of time as applied, lived and experienced.

This contextualises my research inquiry.

The fellowship was split in to two chapters. The first chapter involved a deep exploration in to global discussions – alongside fellow Futurist in Residence Mike Radke visiting from the US, and collaborator @ MOD. Kristin Alford. Together we tested the notion of what it means to imagine futures from particular place-based vantage points, and how our cultural/discursive formations equip us with (and also deny us) tools to do this. We explored place-based experiences (Adelaide and surrounding regions) and the role of place in directing future-making processes. As members of the global network FORMS (Futures Oriented Museum Synergies), we discussed the importance of global networks to drive and shape future making and the significance of conduits to connect global to local thoughts, ideas and experiences. This introduced the idea that place matters.

Within this small group, we discussed the role of museums in this work, and the changing dialogic relationships between museums and their visitors. We observed visitors to MOD. and posed questions around using public cultural spaces to introduce alternative futures. This exercise drew an attention to the processes of generational change/transitions/transference as a critical mechanism for future-making.

We spent time undertaking regenerative land-management work at Yundi Nature Conservancy, knocking back phragmites (common reed) to support a rebalancing effort to return the swamplands back to ecological strength. This work is also – and essentially – cultural. Hearing from Ngarrindjeri Traditional Owner Mark Koolmatrie and his relationship with land owner, agricultural scientist and natural resource economist John Fargher, they demonstrated and showcased a model of two-way minded custodianship that was befitting to the Fleurieu Peninsular swampland south of Adelaide. They showed us how place matters.

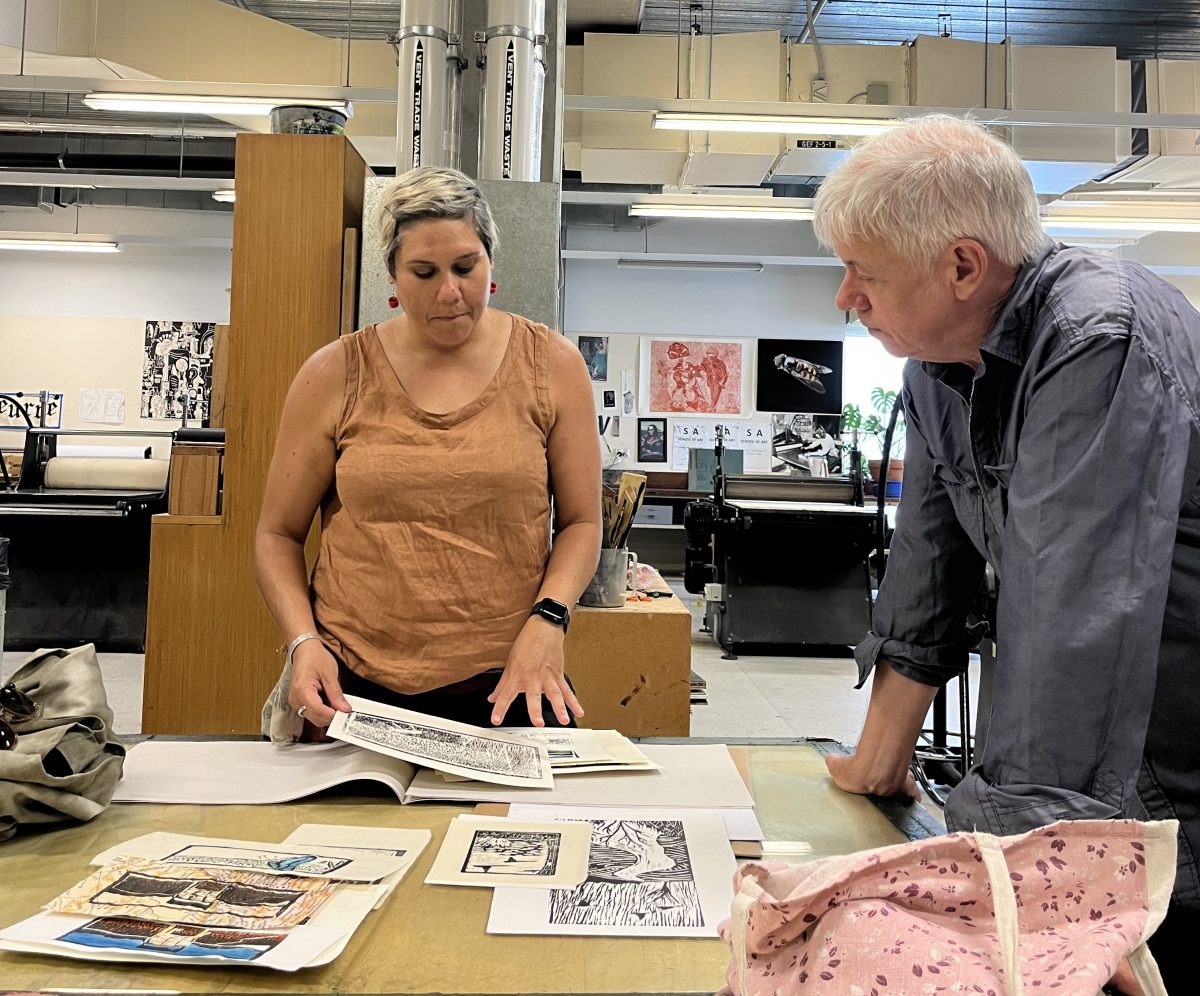

I have over the past few years worked with woodblock printmaking as a way to visualise and articulate ideas. Excitingly, I had the opportunity to use printmaking during my time at UniSA as a mechanism to investigate and visualise the bringing together of linear and cyclical time processes. A grateful acknowledgement to Brooke Ferguson of MOD. and Stephen Atkinson, Program Director at UniSA Creative for the serendipitous alignment and energising time spent in the studio!

A highlight was devising a synchronised printing process with Stephen prompted by the melding together of cyclical and linear time – visualised and explored as ‘slinky time’! Recursive, reverberative and collective: a printmaking jam session. As well as using printmaking as a creative process to investigate and visualise slinky time, we also used it to ask questions around the tensions between individual and collective cultural practice. And how to introduce collective accountabilities to a process like printmaking – and by extension, future-making.

The second chapter involved a block of time spent at the Pembroke School. Taking the opportunity to test some ideas and new language on a 12-18 year old age group in a classroom context, I visited many classes and explored many different dimensions of the enquiry, the breadth of which can be seen below.

To finish Chapter 2 of the fellowship, we returned to Yundi to again rebalance a different area of the swampland. This time, scaling back the bracken fern and seed-harvesting for future plantings. A final acknowledgement to John for his invitation and hospitality. A bountiful lunch table full of John’s homegrown produce is a beautiful gesture towards the benefits of a thriving ecological balance of native and introduced species to sustain healthy lives.

Kristin and I then briefly returned to the printmaking studio with Stephen to consolidate some of the learnings and ideas gathered through the fellowship. This time was incredibly memorable and laid down an ongoing conversation which I will look forward to continuing. We are discussing applying these techniques and ideas in a printmaking process held in another location. We will consider further how place is manifested and articulated in the prints we produce together.

The fellowship concluded with a trip to the Kanyanyapilla property in McLaren Vale. Here Kaurna Traditional Owner Karl Telfer is applying a cultural regenerative approach to restore the balance of land, ecology and belonging. A final expression of gratitude to Karl for the lasting impression of the importance of attending to belonging in any future-making process.

A sincere thank you to everyone who was part of this iterative, creative and inspiring journey.

To the entire wonderful team at MOD. Craig Batty – Executive Dean, UniSA Creative. Sophie Murray (Dieri and Arabana) and the Indigenous staff network at UniSA. Nici Cumpston (Barkandji) – Curator, Art Gallery of SA. Amanda Bourchier, Libby Twigden, Georgia Appleby, Michael Ferrier, Peter Bernard and the whole Indigenous student network at Pembroke School. Mark Koolmatrie (Ngarrindjeri) Traditional Owner and John Fargher at Yundi Nature Conservancy. Stephen Atkinson – Program Director, Contemporary Art UniSA. Karl Winda Telfer (Mullawirra Meyunna), Senior Cultural Custodian and Traditional Owner. Mike Radke – The Ubuntu Lab (and together with) Kristin Alford – Director: MOD. Family in Robert Alford and Tilly Alford. Futurists, collaborators and friends.

Hear from the other Futurists-in-Residence participating in the program: